-

Getting Started

-

Governance

-

Funding

-

Financial Management

-

People & Volunteers

-

Policies & Procedures

-

Wellbeing

- Other resources coming soon

-

Strategic Planning

-

IT & Technology

- Other resources coming soon

-

Administration & Operations

-

Marketing and Communications

- Other resources coming soon

-

Measuring Your Impact

- Other resources coming soon

Governance Guide

SociaLink’s Governance Guide is available to download in full using the button below, or you can browse the 12 sections below using the Table of Contents on the right. ➡️

1. Introduction

Being a trustee on a board or committee of a not for profit organisation can bring lots of exciting opportunities as well as specific roles, responsibilities and challenges.

It is a hugely important role as the head of an organisation; everything you do or don’t do will have an impact on it, its staff, volunteers and the community you serve, for better or worse.

This governance resource aims to help you whether you are involved with a small, local entirely voluntary organisation, or one that employs a few staff or is a larger employer. It has brought together in one place information about what are considered the main aspects of governing an organisation. It has collated information from lots of excellent governance resources and guides and provides links to these as well as to specific tools.

SociaLink’s Mapping the Social Sector Project identified that 14% of the 144 organisations interviewed were keen to grow their skills and knowledge in governance. Even if it wasn’t highlighted for others, there are always things to learn about good governance. Being a trustee or board member may be challenging but remember you are not alone, as noted there are lots of people serving on committees and boards in the social sector in New Zealand – and there is a lot of support, knowledge and tools to support you and your colleagues.

Note about use of terms:

In this resource the terms ‘board’ and ‘management committee’ both refer to the governance structure of an organisation. The terms ‘board member, ‘trustee’ or ‘management committee member’ refer to people with a governance role and are used interchangeably.

Definitions and Information

What is Governance? Key Elements

‘Governance is Governance’ no matter your organisation’s size or circumstances. There is no one approach, right or best way to govern an organisation – every organisation is different, with different situations and circumstances, structures, histories and cultures. Stages of growth vary too from fledging organisations to well established ones, and that also means there may be a different focus at different times. Similarly all organisations face challenges and can find themselves getting into difficulties, whether long established or new, a small community group or a national body.

No matter your size or stage of growth, in following good governance principles and practice you will be better placed to navigate those challenges and steer a good course to fulfil purpose and safeguard your organisation. There is no universally agreed definition of governance but these are key elements for all governing bodies:

- Ensures your organisation complies with all legal and constitutional requirements

- Sets strategic direction and priorities

- Sets high-level policies and management performance expectations

- Characterises and oversees management of risk

- Monitors and evaluates organisational performance in order to exercise its accountability to the organisation and its members/owners.

Boards are in a position of trust – holding in trust the organisation’s physical and intellectual assets and the efforts of those who have gone before, preserving and growing these for future generations. (from ‘Nine Steps to Effective Governance: Building High Performing Organisations, Third Edition, Sport New Zealand’ see www.sportnz.org.nz ).

https://www.charities.govt.nz/reporting-standards/statutory-audit-and-review-requirements

Extra Dimensions for Māori Organisations

Although good governance principles and practices are universal, no two organisations are ever the same. There are also particular characteristics of Māori organisations which bring extra dimensions to the practice of governance.

Governance for Māori organisations may require consideration of the following:

- Purpose of the organisation

- The importance of tikanga and values

- Long-term view

- Appointment of board members

- Board dynamics

- Involving owners in decision-making

- Commercial use of assets

- The Treaty of Waitangi

- Use of Māori terms

- Business Failure – Public Relations

Read the full text here: Te Puni Kōkiri (Ministry of Māori Development)

Other information specific to Māori organisations:

1. Effective Governance – Te Puni Kōkiri (Ministry of Māori Development)

2. Fiona Cram and Kataraina Pipi have co-authored several influential works on Māori governance, kaupapa Māori research, and culturally grounded evaluation practices:

Kaupapa Māori Governance: Literature Review & Key Informant Interviews (2003)

- Authors: Mera Penehira, Fiona Cram, Kataraina Pipi

- Overview: This foundational report explores Māori governance through a kaupapa Māori lens. It combines a literature review with interviews from key informants to identify principles and practices that reflect Māori values and aspirations.

- Themes:

– Self-determination and tino rangatiratanga

– Tribal and community leadership models

– Biculturalism and intercultural communication in governance

- Commissioned by: Te Puawai Tapu and Katoa Ltd https://www.katoa.net.nz/publications

3. Māori Governance Toolkit Videos – Community Governance Aotearoa

Why is Good Governance Important?

- Effectiveness – your organisation will more likely achieve its purpose

- Moral and social responsibility – honouring the work of previous board members, staff and volunteers, appropriately spending money donated or granted to you in good faith

- Efficiency – as the head of the organisation, dealing efficiently with roles and responsibilities and challenges will have a flow on effect

- Leadership – good governance provides a model for the rest of the organisation and enables it to get on effectively with its purpose

- Duty of care –your organisation will have legal obligations and a duty of care towards staff, volunteers, as well as to clients and their families or boarder community

- Legal responsibilities – ensuring fulfilment of legal requirements, for example on financial accountability or health and safety will reduce legal risks to individual trustees and your organisation

- Sustainability – looking at the horizon and what’s coming will help your organisation navigate ups and downs more successfully

- Recruitment and retention – you will be in a better position to find new trustees/committee members and staff – word gets around about how organisations are governed/managed

- Personal satisfaction – it will be more rewarding – no-one goes on a board with the intention of being frustrated, disappointed or to get in strife!

Resources, Advice and Training

There is lots of advice, training, support and resources on governance and related matters. These organisations providing information and support are listed in alphabetical order:

- Charities Services (Department of Internal Affairs) www.charities.govt.nz

- CommunityNet Aotearoa www.community.net.nz

- Exult www.exult.co.nz

- Governance New Zealand www.governancenz.org

- Institute of Directors www.iod.org.nz

- LEAD Centre for Not for Profit Governance and Leadership www.lead.org.nz

- Not for Profit Resource www.not-for-profit.org.nz

- Project Periscope www.periscope.net.nz

- Societies and Trusts OnLine (under the Companies Office) www.societies.govt.nz

- Sportnz.org.nz www.sportnz.org.nz

- Stellaris (Tauranga based) – Quality Governance, Education, Expert Business Advisers. www.stellaris.co.nz

- Te Puni Kokiri (Ministry of Māori Development) www.tpk.govt.nz

Good Governance, What’s Involved?

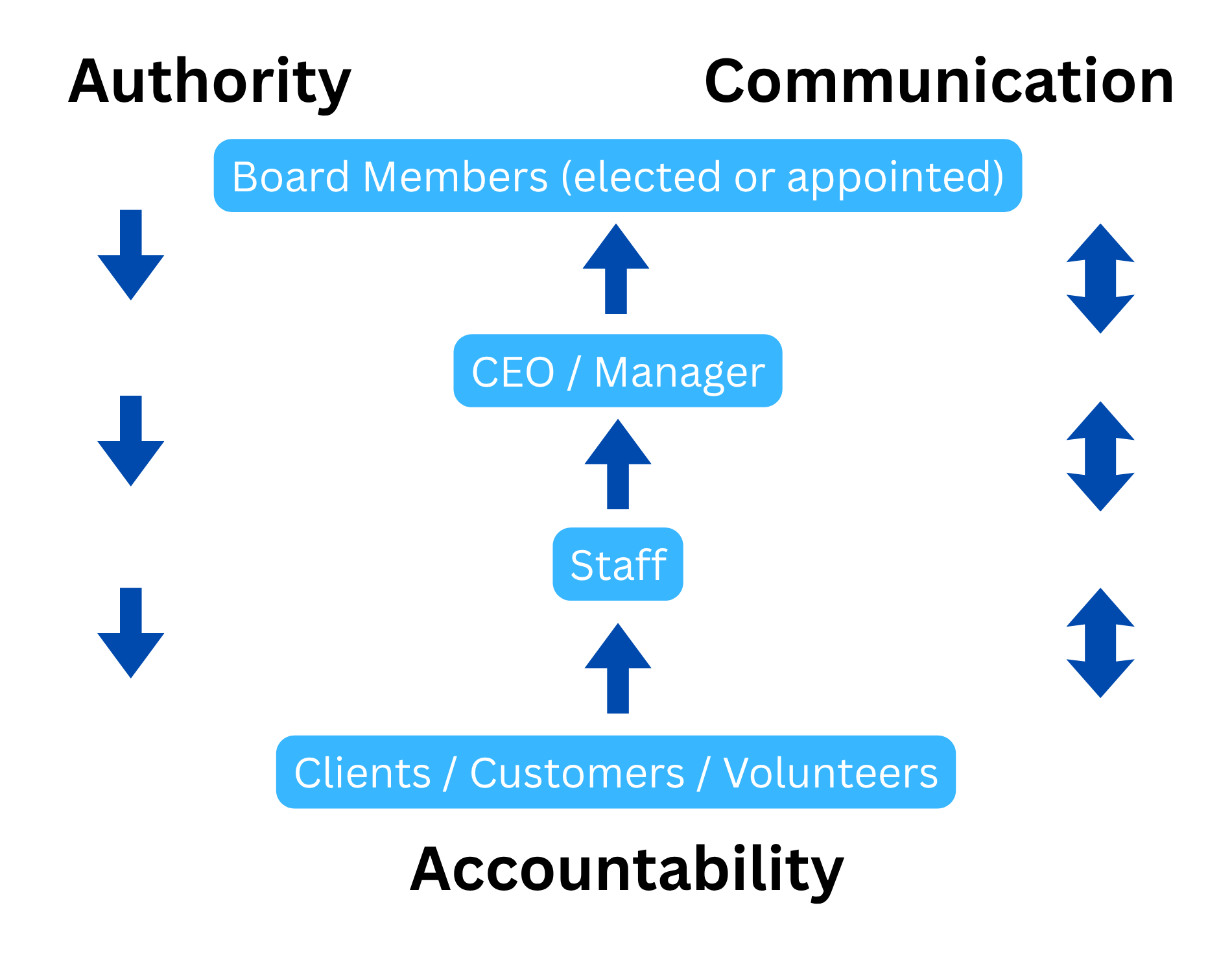

The role of the Board is to ensure things are done, not necessarily doing it all itself. The board or ‘management committee’ should be clear about its responsibilities and expectations.

You have been entrusted with the responsibility to look after the organisation. The trust you have accepted – by agreeing to come on the board, or by being elected or appointed – is called a fiduciary relationship, which means you have a number of duties. Briefly, you have to act in good faith and with due care and diligence.

What Does Fiduciary Duty or Responsibility Mean?

The board has a fiduciary duty to the organisation and its wellbeing. As a board member you must:

- Exercise a duty of care

- Act honestly

- Avoid using your position for personal advantage

- Comply with all relevant legislation and organisation constitutional requirements

- Act in the best interests of the organisation as a whole

(From ‘Getting on Board, a governance resource for arts organisations’, Creative New Zealand, 2014)

2. Roles & Responsibilities

Roles of the Board

- Establish a clear vision, mission, purpose and values for the organisation and review them every so often

- Define and approve strategies for achieving the vision, mission, purpose, programmes and services

- Obtain resources and community support for the organisation

- Provide financial oversight and ensure the organisation meets legal and financial requirements

- Develop appropriate risk management practices and policy guidelines

- Employ the Chief Executive Officer (if applicable), managing all aspects of the recruitment process and employment contract

The following are some of the roles and tasks office holders are typically responsible for:

Chair’s Tasks

- The chair’s role includes running board meetings, ensuring the board does its tasks and operates effectively, keeping the organisation focused on its goals and representing the organisation to others.

- A good board chair provides effective leadership, has the confidence of the board, has a productive working relationship with the CEO if there is one, a good understanding of the purposes and operational challenges of the organisation, skills to build a cohesive board and is an effective ‘conductor’ of meetings.

- If your organisation has a CEO, the chair’s role includes being a sounding board for the CEO’s proposals, ideas and concerns, leading recruitment, and in some circumstances termination of a CEO’s employment.

- The chair oversees, in partnership with the Board, that the appropriate, lawful and expected actions are done for the organisation to achieve its purpose. Read more about chairing a board.

A further information sheet Three Cheers for the Chair, developed by Exult, is also useful.

Secretary’s Tasks

(Some relate to the type of organisation)

- With the Chair, the secretary prepares the agenda in advance of Board meetings, organises meeting papers for distribution before the meeting, takes minutes and circulates them at Board and Annual General Meetings

- The secretary usually deals with correspondence in line with Board decisions

- Ensures preparation and adoption of board policies, if applicable, keeps a register of members and handles procedures for new member admissions, resignations and discipline/suspension and expulsion

- Organises General Meetings and notifies members in advance, receives nominations for positions on the Board

- Keeps all books and documents associated with the organisation (eg trust deed, constitution, copies of minutes), liaises with regulators such as Charities Services, as required produces in partnership with the board other documentation on correspondence and policies/plans

Treasurer’s Tasks

- At each board meeting the treasurer reports to the board on the financial situation and any variation from the approved budget, prepares accounts for auditing, and reports to the AGM on the organisation’s financial situation

- Advises the Board on financial matters, including fundraising

- Ensures that appropriate financial policies and procedures, such as financial controls, are adequate and safeguards against fraud are in place, ensures risk management strategies are in place, oversees investment strategy and that expenditure limit approvals, and checks are in place and fully documented

- Depending on organisational size, the treasurer may collect and receipt all money received

Employing and Supporting a Chief Executive

The interrelationship between a board and chief executive is critical to governance success. Think of it as a partnership in which each respects the other’s roles, responsibilities and prerogatives.

If you are a small organisation currently without a chief executive, you will need to clarify if you want or need a chief executive or an administrator. You might decide that the board volunteers will carry out operational tasks as well as being the governing body.

If you do decide to recruit firstly:

- Make clear what the chief executive is to achieve – the organisational outcomes you want which the chief executive then carries out operationally to achieve

- Determine the authorities that the chief executive will be granted – policies and protocols to guide them (for example around financial control)

Good chief executives are in high demand. Just when things are going well, you may find you need to replace them

Key elements in a successful relationship between the board and chief executive include:

- Role clarity

- Mutual expectations must be explicit and realistic – what the board and chief executive want of each other

- Reporting and information requirements

- A fair and ethical process for chief executive performance management

- A sound chief executive-chair relationship

- Helping the board understand the risks faced by the organisation

The chief executive’s two primary roles at board meetings are:

- helping the board understand and address the future by providing advice and support to the board’s discussion and decision making; and

- helping the board analyse and understand the past and providing evidence that everything within the organisation is as it ought to be

(Based on advice in Nine steps to effective Governance, Sports NZ)

Policy Development Responsibilities

A policy is an agreed basis for action, made ahead of time. It provides guidance and expectations on the course of action.

Policies are a vital form of ‘remote control’, allowing the board to influence what goes on in the organisation without having to make every decision. They should be seen as living documents and not as ‘tick box and put on the shelf’ exercises. They should be reviewed every so often to ensure they are fit for purpose.

Rather than work on policies it might be tempting to just get on with what seem more pressing issues, and ‘get back to policies later’, especially if you are in a small organisation where board or committee members are doing a lot of hands-on management related work.

Unfortunately this can mean much policy making becomes reactive, developing in ad hoc fashion to solve a particular problem after it has occurred. Examples could be developing policy over conflicts of interest on the board or if it’s revealed the chief executive is occasionally using organisational credit cards for personal matters.

An ad hoc approach can mean a policy becomes too tailored to resolving a specific issue and can also involve uncomfortable personal discussions.

It is better for the board to be proactive and work in advance as a team to think about and develop policies, so they act as guides and provide clarity about functions and expectations.

The constitution or rules is an important starting point for the development of policies, as well as the board’s legal and other responsibilities. Some boards develop a board charter which sets out the responsibilities and expectations of the board and board members. Whatever approach you take, have them in one document, rather than scattered.

One policy framework widely used is based on the concept of policy governance developed by John Carver (John Carver, Boards That Make a Difference, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006). He has four policy categories that cover the core elements of the board’s job. The first two are related to the board’s job and its role as an employer; the third to preventing and minimising harm to the organisation and the fourth to the impact of the organisation in the world.

- Governance Process policies – these define the scope of the board’s own job and design its operating processes and practices.

- Board-Chief Executive Linkage policies – these define the nature of the board-chief executive relationship, specifying the details and extent of the board’s delegation to the chief executive and methods to be used in determining chief executive effectiveness.

- Executive Limitations policies – these define the constraints or limits the board wishes to place on the freedom of the chief executive has (and by implication other staff and volunteers), to select how he or she will achieve the outcomes for the organisation that the board has identified. These are written in a proscriptive way (telling the chief executive what they can’t do or shouldn’t let happen, rather than what they can do). This approach gives greater control to the board and at the same time offers more empowerment for the chief executive.

- Ends (or Outcomes) policies – these address the purpose of the organisation and set the outcomes or strategic results to be achieved by the organisation.

The chief executive and other key staff should participate in the development especially of Ends/Outcomes policies and Executive Limitations policies. You might want to bring in an outside consultant to help speed up the process, but it is important that the board and staff discuss them properly as they apply to your organisation. Once they are adopted, staff and all board members are bound by them. They enable decisions to be implemented by the organisation even when the board members may not be unanimous on a particular issue.

Community Net Aotearoa’s Guide on Policy Development

Board charter and policies Online resources available

Policy Bank Institute of Community Directors Australia

Financial Responsibilities

Boards have a financial stewardship responsibility for the organisation. While there is a tendency for board members to rely on board colleagues who have particular financial or accounting expertise, all board members are accountable for the financial well-being of the organisation.

It’s prudent to get training so you can ask informed questions and understand the organisation’s financial matters. The board should ensure this happens.

The board should develop policies to support its financial stewardship. They might include policies that set out limitations and expectations for the chief executive on:

- spending authority (eg the maximum level at which chief executive can spend without needing to seek board permission)

- budgeting/financial planning (e.g. CEO shall not use surplus funds inconsistent with the boards’ use of reserves policy)

- protection of assets (e.g. CEO shall not subject buildings and equipment to unauthorised or improper use, wear and tear or insufficient maintenance, or fail to have adequate insurance for prudent risk management)

Other policy areas could include policy on investments, working capital, net assets and reserves, and general guidelines for financial management, employee remuneration and benefits.

The board should get regular financial position and performance information so it can take remedial action if necessary.

CommunityNet Aotearoa’s guide on financial management:

https://community.net.nz/resources/community-resource-kit/introduction-to-financial-management/

The External Reporting Board (XRB) provides accounting standards for financial reporting for not for profit organisations (Tier 1,2,3,4), reporting templates, tips and FAQ at this link:

https://www.xrb.govt.nz/accounting-standards/not-for-profit/

Capacity Building Webinars on finance

https://ngo.health.govt.nz/resources/ngo-council-webinar-project/webinars-finance

A blog on fraud and tips to avoid it from Charities Services:

https://www.charities.govt.nz/news-and-events/blog/fraud-in-the-charitable-sector/

Resources:

Nine Steps to Effective Governance – Sport NZ

Getting on Board – a governance resource for arts organisations.

The Troublesome Board Member, National Center for Nonprofi t Boards, Washington – Bailey, M 1996

Perfect Nonprofi t Boards: Myths, Paradoxes and Paradigms, Simon and Schuster Custom Publishing, Needham Heights – Block, SR 1998

Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofi t Boards, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken Chait, RP Ryan, WP & Taylor, BE 2005

Board charter and policies Online resources: www.sportnz.org.nz

A series of ‘Getting on Board’ webinars by Creative New Zealand can be found here, covering the following topics:

- Governance with impact

- Chairing the board

- Information for good governance

- Decision-making at board level

- Board succession and transition

- Board dynamics

- Health and safety and the role of the Board

- Boardroom excellence – the Chair/Chief Executive relationship

Free Governance 101 online training – SportNZ (on the SportTutor learning platform), available to the wider Not for Profit sector, 2-3 hours

Policy Bank – Institute of Community Directors Australia

Trustees Liability Information – Tonic Magazine article, Exult

3. Board Composition

As a general rule it is inappropriate for staff, including a chief executive or manager, to serve on the board of the organisation that employs them. This ensures there is no role confusion, each can focus on their special contribution to the organisation and wear just one hat, and accountability is not compromised.

In smaller organisations with few or no employed staff, including both small not for-profit organisations and commercial ‘start-ups’, board members may need to fill both the governing role and all or part of the operational functions.

This places a considerable burden on board members but it is the reality of governing a small organisation. Founding trustees often find themselves not only investing their own money in the business but also filling both operational and governance roles. As organisations grow and are able to employ specialist staff, board members can confine their involvement to governing. Where board members do need to assist with operational tasks, they should appreciate that their role is as an operational volunteer, not as a board member offering assistance.

Trustee Competencies

Strategic Thinking Skills

Highest on the list of trustees skills is the ability to adopt a strategic perspective, particularly an ability to look beyond operational issues and work towards a vision for the future.

They should also have an understanding of organisational structures and systems

Trustees should have a basic understanding of how organisations should be structured and operated in order to deliver appropriate results.

Financial Management

Every trustee should be comfortable with traditional financial statements, understand the current financial position, areas of risk and future financial requirements.

Knowledge of General Legal Issues

An understanding of the relevant legislation and regulatory environment within which the organisation operates.

Knowledge of the Business of the Organisation

Every trustee must accept a personal responsibility to remain up-to-date in their knowledge about the sport or the sector so this can be applied in the board’s strategic decision making and performance monitoring.

Commitment to the Organisation’s Mission and Values

Because of its stewardship role, all board members must demonstrate tangible commitment to the organisation’s mission and values, knowledge and appreciation of te Tiriti o Waitangi, te Ao Māori and other cultures that are represented in the area you provide services to.

A Commitment to Governing

Trustees should understand the difference between governance and management.

Personal Attributes

Ethical standards

Highest on the list of personal attributes must be those associated with a commitment to personal integrity and corporate governance ethics.

Independence

The board must reflect a diversity of opinions and experience. Collective judgements are enhanced by sound independent thinking brought together around a shared purpose.

Interpersonal skills

The ability to listen to the viewpoints of others, to question effectively and to challenge constructively are all essential boardroom skills.

Leadership skills

Willing to take leadership roles as necessary, in committee work, representing the organisation in public, leading specific discussions or project work.

Ability to understand and relate to stakeholders

Board members have the ability to understand and respond to the various positions of stakeholders in a sensitive, reasoned way.

Ability to recognise competing interests

Board issues and processes are viewed through the lens of principle rather than the subjectivity of personal impact or implication. Real or potential clash of interests should be acknowledged and appropriate steps taken to maintain ethical standards.

Commitment

Preparedness to commit the necessary time both in an out of the board room.

For a template commitment letter for new trustees to sign, see here: Commitment letter

Board of Trustees ‘Needs Matrix’ Template

This ‘needs matrix’ has been designed to assist in board (succession) planning to assess the overall strengths and weaknesses of the board’s current membership. Because of the nature of the data collected, however, it may also be used as a starting point for a wider evaluation of board effectiveness.

Key Steps:

- The board should agree the desired skills, attributes and experience needed for the effective governance of the organisation. Appropriate weightings (if any) should also be agreed.

- Each director should then complete the matrix, assessing themselves and every other board member against each of the desired characteristics, using the five-point scale described below.

- Ideally, someone who is independent of the board (for example, a governance consultant), should receive and collate the responses, to produce two separate reports:

- A board composite report that shows total scores for each (unnamed) board member and the total score for the board against each of the desired characteristics given the agreed weightings. This is for discussion by the board as a whole; and

- A report for each individual that reveals their own self-assessment compared to the average rating given by their colleagues. If agreed in advance it is worthwhile revealing individual scores to the chair for discussion with those individuals.

- The board should discuss the implications of this analysis of the current board composition in the light of the challenges facing the board. It should develop a strategy for strengthening the board as it seems indicated.

Scale Description

5 Exceptional competence

Possesses exceptionally well-developed and relevant skills and abilities, as well as the appropriate personal qualities in relation to this criterion. Demonstrates outstanding performance, perhaps supported by extensive experience (10 years +) and relevant formal qualifications.

4 Fully competent

Possesses exceptionally well-developed and relevant skills and abilities, as well as the appropriate personal qualities in relation to this criterion. Demonstrates outstanding performance, perhaps supported by extensive experience (10 years +) and relevant formal qualifications.

3 Mostly competent

Possesses relevant skills, abilities and personal qualities sufficient to demonstrate a generally adequate level of competence. Further experience and/or professional development would boost performance.

2 Basic competence only

Demonstrates some skills, abilities and personal qualities relevant to the criterion. Professional development required to become competent.

1 Minimal/no competence

Unable to demonstrate adequate skills, abilities and personal qualities for this criterion.

- Establish a clear vision, mission, purpose and values for the organisation and review them every so often

- Define and approve strategies for achieving the vision, mission, purpose, programmes and services

- Obtain resources and community support for the organisation

- Provide financial oversight and ensure the organisation meets legal and financial requirements

- Develop appropriate risk management practices and policy guidelines

- Employ the Chief Executive Officer (if applicable), managing all aspects of the recruitment process and employment contract

Resource:

Top Tips for Getting the Right People on your Board – Exult

4. Culture and Ethics

The Board sets the tone for ethical and responsible decision-making throughout the organisation. Codes of conduct are one way of agreeing to setting out expected standards of behaviour and ethical conduct. The board and its members have a leading role in promoting a healthy culture for the organisation they serve. Culture includes shared values, norms, practices and core beliefs which shape ‘the way we do things around here.’

The actions, conduct and behaviour of the Board, as the head of the organisation, will influence its culture and its reputation. Not for profit organisations usually start with a good reputation, after all they are acting for the benefit and interests of others. Reputations are based on perceptions and opinions that people have, based on past behaviour or character. Boards are ultimately responsible for the development and enhancement of the organisation’s reputation. Board conduct and ability affects the organisation’s reputation, whether it delivers on its purpose, staff morale, ability to attract and retain staff and volunteers, level of risk taking, and potential exposure to legal or regulatory action against it.

Codes of conduct are one way boards set out expected standards of behaviour and ethical conduct for their members. Often desirable and expected behaviour is unwritten and includes:

- Reading board related documents before the meeting

- Arriving on time and staying until the end of meetings

- Not monopolising discussion or talking over others

- Responding to emails and other board communication

- Giving each board member the opportunity to speak

- Asking questions is not discouraged or belittled

- Board issues are dealt with in the boardroom meeting and not in private conversations

Resources

Drawing up a code of ethics:

https://www.communitydirectors.com.au/help-sheets/drawing-up-a-code-of-ethics

Patrick Moriarty’s tips on creating a healthy organisational culture – Institute of Community Directors Australia executive director and head trainer Patrick Moriarty explains how to spot if your organisational culture is turning sour, and how to turn things around:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPqqSYoNUls&feature=youtu.be

Institute of Community Directors Australia – People talking about organisational culture:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUP-ZBQCMsU&feature=youtu.be

SportTutor learning platform’s New Governance 101 course has a module:

https://sportnz.org.nz/managing-sport/search-for-a-resource/news/new-governance-101-online-training- now-live

https://sportnz.org.nz/media/1187/boards-role-in-organisational-culture6.pdf

5. Strategic Planning

The board is responsible for developing a strategic plan for the organisation. The strategic planning process enables those involved in the organisation such as board members, staff, volunteers, members and other stakeholders, to think through and document what it is doing, for whom, and why it is doing it.

The aim is to help your organisation do a better job. It is also important for public accountability – if you want the public to support you with money or for your organisation to be relevant to your community of interest (the people/groups you want to help), you need to show why you are a safe bet.

General Information

Some Useful Questions to Ask When Strategic Planning or Reviewing Your Existing Plan:

- What is our purpose, our reason for being? (What is our ‘Big Idea’?)

- If this organisation did not already exist, why would we create it?

- Have we fulfilled our purpose? Is it time for us to close the doors? Has the world moved on?

- Who are we doing this for? Who should benefit? What difference or outcome will we make?

- What is the essence, ethos or spirit of this organisation?

- What is important to us?

- Where do we want to get to?

- What do we want to become?

Spending time asking these types of questions will also help you find out the perspectives of those involved which will be very useful. It is also good to do this around the board table from time to time. By clarifying what your organisation’s ‘end goal’ is, or what you really want to achieve, the board will move away from ad hoc, short term decision-making into a higher level, more strategic and planned approach. Without the benefit of such planning, decision-making by boards is often personally driven by individual members’ experience and knowledge, or relies too much on the manager’s operational perspective because ‘they are at the coalface, have looked into this and must know what’s best to do.’ Another benefit of strategic planning is your CEO/Manager will have a clear plan to put into action, rather than having to guess what the board will want or wait for board approval before they can act.

Creating the Strategic Plan

There is no perfect formula but most organisations typically work through the following set of activities:

- Environmental scan or situational analysis

- Plotting direction

- Action Planning

1. Environmental Scan or Situational Analysis

This activity looks at and analyses your organisation’s current relationship to the broader social, political and economic environment. For example, there may be a more urgent issue to focus on, a shift in demographics, a new organisation on the scene, a change in government policy. Here are some tools that will help you through the process. You can then look at how your organisation is placed to meet the challenges identified in the environmental scan. Using a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats), for your organisation is one way of doing this.

2. Plotting Direction – Your Vision, Mission, and Goals

Following the environmental scan, you will need to decide how to respond to the issues and opportunities you have identified. There will be some strategic choices you can make. The direction includes a vision and a mission statement that typically contains the basic guiding principles for board and staff.

- Your vision refers to the future, what you want to become or achieve

- Your mission is about today, what you are doing

For example the [fictional] HuffPuff Swimming Organisation’s vision is “All children will be safe in the water”. Its mission is “To reduce childhood deaths from drowning by providing free swimming and water confidence lessons to all children under ten in the Western Bay of Plenty, taught by qualified swim instructors.”

Examples of Vision and Mission statements:

Heart Foundation:

Vision: Hearts fit for life.

Mission: To stop all people in New Zealand dying prematurely from heart disease and enable people with heart disease to live full lives.

TED talks:

Vision: We believe passionately in the power of ideas to change attitudes, lives and ultimately, the world.

Mission: Spread ideas.

Plotting direction includes setting goals (which could also be called objectives or outcome statements). They should be SMARTER – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound, Evaluated and Reviewed.

Resources

This Community Net link below provides a breakdown of strategic planning steps and some tools to use: https://community.net.nz/resources/community-resource-kit/strategic-planning/

Example of community organisations’ strategic plans:

Foundation North – http://www.foundationnorth.org.nz/

SociaLink – Te Korowai Kahui Strategic Plan

Heart Foundation – https://www.heartfoundation.org.nz/our-strategic-plan

3. Action Planning

This third step includes identifying specific activities to achieve the goals or objectives, the monitoring/evaluating of progress and results, and setting a budget. These can then be built into an operational plan. They should be flexible enough to respond to new developments.

6. Risk Management

No matter how small or big your organisation is, risk management is a board responsibility. You can delegate some risk related tasks to management but overall the board is responsible for the organisation’s approach. Think systematically about all the possible risks, problems or disasters that could affect your organisation and its staff, clients, families, volunteers, or the public. Put in place procedures to avoid the risk, minimise it or cope with its impact. Risk management also means making a realistic evaluation of the true level of risk (how likely it is to happen to your organisation).

Dealing with Risk

How to Identify Risk

Some ways to deal with risks are keeping a risk register, having insurance, developing policies and procedures, staff and volunteer training, and ongoing monitoring.

Three questions are useful:

- What could go wrong?

- What will we do to prevent it?

- What will we do if it happens?

Some Categories of Risk to Think About

- Compliance risks (e.g. failure to lodge statutory information in allowed time, legal requirement to keep records, privacy and confidentiality of information)

- Financial risks (e.g. loss of funding, insolvency, fraud, expense blow-out, inaccurate or lack of records, lack of internal checks and balances)

- Governance risks (e.g. ineffective oversight, not having clear policies and procedures, lack of responsiveness to mana whenua)

- Operational risks (e.g. poor service delivery, potential to cause harm to people, loss or corruption of digital information and data, cybersecurity risks, staff or employment issues such as wrongful dismissal or harassment,volunteers’ lack of training or screening)

- Environmental, including event risks (e.g. natural disasters and states of emergencies)

- Physical spaces and equipment (eg fire, flooding, workplace health and safety issues, theft or misuse)

- Brand and reputational risks (e.g. due to worsened stakeholder or community perceptions, major event failure, criticism of your performance via traditional or social media)

- Strategic risks (e.g. not keeping up to date with environmental scans, poor consideration of Treaty of Waitangi application to the organisation’s purpose, stakeholder behaviour change, increased competition for funding)

Resources

This link provides a risk scoring matrix and an example of a risk register:

https://community.net.nz/resources/community-resource-kit/2-7-planning-/

This link is to a Risk Management Toolkit resource developed for arts organisations and includes templates for risk registers:

http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/development-and-resources/risk-management-toolkit

7. Performance of Your Organisation

Whatever your organisation’s size or purpose, a board is responsible for its overall performance. You need to know if the organisation’s resources are being used efficiently and effectively.

Identify some key performance indicators (KPIs) or key result areas (KRA) to track progress. They should be linked to your strategic plan and be a mix of financial and non-financial measures.

Measures

Measures should be:

- Meaningful to your organisation

- Capable of being measured and acted upon

- Timely

- Cost effective to produce

- Capable of allowing comparisons (e.g. over different timeframes, between projects, with external benchmarks)

- Simple (where possible)

Audit and Risk Committees

An audit and risk committee can be a powerful advisory group to help an organisation manage its risk. By applying external, independent perspectives to the risks, issues, and challenges facing an organisation, the committee can help the organisation to manage the variability of its delivery of outputs, impacts, and outcomes. The Office of the Auditor General has a wide range of information about audit committees here, including principles and tools and tips.

KPIs

KPIS are easier to identify if your mission and goals are clear, achievable and measurable. KPIs could be related to:

- Fundraising – e.g. Fundraising from donors, donations and donor growth, fundraising return on investment (ROI – comparing the number of dollars coming in per dollars spent on fundraising)

- Marketing and Communications – e.g. number of website page views, email opens and click-through rates, number of newsletter subscribers

- Programme/Service Delivery – e.g. number of clients serviced, programmes/activities attended, satisfaction rates, pre and post scores measuring changes in knowledge, skills; abilities, behaviours

- Human Resources – e.g. employee retention rate, employee satisfaction rate, percentage of performance goals met, absenteeism rate

- Financial – e.g. year over year growth; operating surplus/deficit

Resources

See this blog on ‘20 KPIs for your Nonprofit to Track’- it includes how to measure and calculate them:

https://donorbox.org/nonprofit-blog/kpis-for-your-nonprofit/

Programme/Service Delivery – For more information on social impact KPIs see this blog “Measuring Nonprofit Social Impact: A Crash Course”:

https://donorbox.org/nonprofit-blog/measuring-nonprofit-social-impact/

A major research report looking at how value is measured in the non-profit sector in Aotearoa New Zealand:

https://sportnz.org.nz/managing-sport/search-for-a-resource/news/true-to-label

8. Board Effectiveness

Your board or committee will be more effective and more satisfying to serve on if it has a sound recruitment and induction process for members, good planning, and well-run meetings. It is a good idea to also regularly review your own performance as a board or management committee. The following are some suggested areas where effectiveness can be enhanced.

An Appropriate Board Structure

Induction/Orientation for New Board Members

A properly welcomed and inducted board member is a quickly productive one who will be pleased to contribute and add value. Don’t leave it to chance for new members to ‘pick up’ what your organisation is about, or what the roles and responsibilities of the board members are. They may have experience as a trustee or may have served on a club committee, or be entirely new to a governance role. Being a trustee of a charitable trust involves legal responsibilities and liabilities which people need to be clear about. They also need to know prior to joining if there are any expectations such as trustees giving a donation or undertaking hands-on fund-raising. Not everyone is comfortable with doing this, but it doesn’t mean they can’t add value in other ways. An orientation package should include documents such as constitution or trust deed strategic plan, policy manual, board code of conduct, key historical points about the organisation, current year to date budget, most recent annual report, any recent newsletters, recent board minutes, and biographical information about board members and if appropriate, staff.

Planning Board Work Activities in Advance

This could include using a simple board calendar and work plan covering (as applicable to your organisation): fundraising events, approval of budget, AGM, Charities Services reporting requirements, board strategy session, policy development or policy review schedule, risk review, performance review of CEO, remuneration review.

Making Decisions

To be an effective board of your organisation, you will want to make sure your decisions are well thought through and well made. This applies whether you are making mainly strategic level decisions, with operational issues left to management, or if you are a smaller organisation where you may be involved in some management level decisions. You still need to know what board business is, and what it is not, and document this in writing. Sound decision making is part of building the credibility and integrity of the organisation to its stakeholders and is part of the expected stewardship role. The following steps are based on Te Puni Kokiri’s helpful resource, Making Decisions: A process guide for boards.

a) Will the board accept the issue? – is it appropriate and has it been brought to the board through the right channels. This gives you the opportunity to be clear about governance and management boundaries and not get bogged down in something that is a management issue or really only of interest.

b) Identify the type of issue – this will help establish what you might need to make a decision. For example is it a standard issue with set procedures to follow such as approving minutes; is a new issue which may need more investigation and more than one meeting while you do that; is it significant where the board is committing to particular plans or actions or expenditure and may need to devote more time on it; or is it a crisis – an unexpected event requiring specific plans and responses.

c) Define what the ‘problem’ is – it’s important to be clear on what the issue or problem or opportunity is. Breaking decision-making into parts can help work through a process more efficiently and help a board be clearer about what series of decisions it needs to make. It reduces the risk going off on a tangent or worrying about how to fund something before you have said yes to doing it.

d) Understand the context – does the potential decision fit with your legal status (e.g. your trust deed if you are a charitable trust) and your strategic plan – they should be on hand for reference. How will it fit in with other plans and commitments the organisation has made, for example take on a new lease? What about external influences like changes in government policy?

e) Gather information, facts and advice – this is part of due diligence as a board member as is asking reasonable questions to collectively ‘stress test’ the idea. You might want to look at a format for written proposals put before the board so that people writing them know what is required. Don’t be afraid to seek external advice. You aren’t expected to know everything.

f) Analyse – keep an open mind – at first glance the proposal may look like the next best thing since sliced bread but it could have been made on faulty assumptions, have risks or unintentional consequences. Seeking views from all board members can help unearth information, assumptions, gaps or misunderstandings. Boards can also consider alternative options, criteria for assessment, weighting, and logical testing. Make your own decisions as a board member but in a respectful way towards other board members and that honours the integrity of the organisation you serve.

g) Make the decision – The role of the chair in facilitating good constructive discussion is important. As well as assessing the analysis, using judgement and considering vision, values and cultural requirements are all aspects involved. Working to find a consensus decision is beneficial. It means the decision has support from the whole board which is then sharing responsibility and accountability, is focused on finding solutions, ensures buy-in, develops positive dynamics and provides leadership, and often supports the culture or tikanga of an organisation.

h) Record the decision – Recording the decision is crucial and should be in the minutes of the meeting. It should be brief and clear but with enough information that it is still meaningful at a later time. You can use specific words to express such as ‘the board resolved to…’; the board ‘agreed’, ‘approved’, ‘deferred’, ‘noted’, ‘sought further information’. The minutes are the official record of a decision and therefore provide accountability. They provide authority for activity, evidence that board members met their governance obligations, and are the key way to show the board is doing its job. They also provide a historical record and source of information.

i) Communicate and get action – Make sure you let people who need to know about the decision, that an action plan is in place and that you receive reports from management on progress against the action plan.

Act Within Rules

Make Sure You Always Act Within Your Organisation’s Rules. Even if you are fairly informal as a governance group, following the rules and procedures of your organisation will save you a lot of trouble:

- Constitutions and policies set out the rules. Have a copy of both at your meetings.

- Make sure you have a quorum (a minimum number of people who must be present for decisions to be valid), for your meetings – if you don’t, decisions made will not be legally effective (for example if at a board meeting you decided to sell an asset, but you didn’t have a quorum, this decision can be challenged).

- Ensure you follow proper process in all decision-making (as stated in your governing documents) – e.g. a resolution is moved, seconded and voted on.

- Document your decisions in the minutes and get the minutes reviewed and approved at the next meeting, noting in writing any amendments by those present at the last meeting. You can then prove you followed the right procedures and can also go back and check your own decisions and reasons. Relying on memories won’t do.

Assessing Performance Regularly

Regularly reviewing your effectiveness as a board can help sharpen your performance. The aim is to improve your quality of governance, discussion and decision-making. This could include using a self-assessment tool or external facilitator, or attending governance training. If there are issues they may be holding the board back, such as chair effectiveness or board conflict an external expert facilitator may be useful. That person could have one to one meetings with board members and then help the board work through the next steps. Enhancing board performance can occur through board orientation for new members, having clear policies and procedures, mentoring, and resources for training and professional development.

Board Professional Development

Continuing to develop or refresh skills and knowledge about governance and about your organisation’s area of interest is beneficial. There are lots of ways to do this, especially with online communication options – YouTube clips, online learning qualifications, podcasts, local courses and seminars, expert speakers and so on. Your board could take a collective approach to this, setting aside time at meetings to discuss needs and learning. Allocating a budget for board development is also a good idea.

Resources

This article from Exult, which help non-profits grow has lots of ideas:

https://www.exult.co.nz/articles/professional-development-for-non-profit-trustees/

Exult also runs workshops on effective meetings and chairing of boards.

https://www.exult.co.nz/workshops/governance-express/

Identifying Conflicts of Interest

As a board member you have to act in the best interests of the organisation. If there is any possible conflict of interest, you have to step aside. You can’t take advantage of your position on the board. Conflicts of interest occur when a board member’s personal interest or loyalties could affect their ability to make a decision in the best interest of the organisation – remember as a board member your duty and responsibility is to the organisation as a whole.

Conflicts of interest include the following:

- When a board member could benefit financially or otherwise from the organisation, either directly or indirectly through someone they are connected or related to

- When a board member’s duty to the organisation competes with a duty or loyalty they have to another organisation or person.

Common situations of conflict of interest:

- The board’s decision could lead to employing a board member or family member

- Board members could gain financially from business, programmes or services provided to the organisation (e.g. if engaged as a consultant, co-owner of a catering company or other supplier used by the organisation)

- Information provided to the board in confidence might give an advantage to a board member’s business (for example when calling for tenders that the board member’s business might be interested in applying for)

Ways to deal with conflicts of interests:

- Keep a register of board members’ perceived, current or potential interests

- Declare interests at the beginning of meetings about any items on the agenda

- When there is a conflict of interest, the affected member does not take part in discussion or decision- making. You have to notify your board colleagues when a conflict comes up, you then can’t speak about the motion and you may have to leave the room while the issue is being discussed

- Boards should act conscientiously, be transparent and document their processes and decisions so if an issue is raised, you can explain why you all took the decision you did

Resource: Conflict of interest – Charities Services

Running Efficient Meetings

This includes having a clear concise agenda, sending out any papers in time for board members to read them, board members reading the papers, an effective meeting chair, relevant, robust and respectful debate, minutes that accurately record decisions and are finalised promptly, and board only sessions without the CEO present.

The chair’s role includes ensuring the agenda and papers are prepared, promoting inclusive debate and appropriate tone during discussions and dealing effectively with dissent and conflict.

Factors contributing to poor meetings include:

- poor performance by the chair

- absenteeism by members

- conflict of interest matters not being appropriately dealt with

- dominant chairs, board members or CEOs taking over meetings/making decisions without sufficient regard for other member’s views;

- disrespectful talk or behaviour towards other board members, not striving to work as a team

- board members seeing themselves as representing particular stakeholder viewpoints rather than the organisation as a whole

- inappropriate agendas and papers (e.g. too detailed, not detailed enough; important information missing or buried; wrong ordering of agenda items)

- not enough time for pre-reading or discussion

Resource: Introduction to meetings – CommunityNet Aotearoa

Avoiding Poor Decisions

Signs that a board’s collective decision making is not as effective as it could be include:

- An inability to explain to members, staff or media why the board made a certain decision

- A feeling that decisions do not represent the best thinking of the board

- A sense the board is rehashing old issues

- Heated discussions based more on opinions and emotions than facts

- Long drawn-out discussions that lose track of the original topic

- Last minute introduction of ‘wildcard’ topics not on the agenda that divert time and attention

- A decision that the entire board agreed to but isn’t in reality supported by every board member

Poor or lack of information, not allowing enough time for good deliberation, cutting off debate, individuals under pressure to make decisions, tiredness, and emotional debate will likely lead to poor decisions. Getting good information, being clear on board responsibilities, setting agendas to have time for important discussions, taking a break if debate becomes heated or tabling the issue until further investigation is done, will help avoid poor decisions the organisation may regret.

What Management Would Like from Their Boards

(Based on ‘What CEOs Really Think of their Boards’ by Jeffrey Sonnenfeld; Melanie Kusin and Elise Walton, Harvard Business Review, April 2013).

- Don’t see risk in personal terms – healthy change or growth may require a level of innovation and risk.

- Do the homework and stay plugged in – and don’t rely too heavily on management for the knowledge you need – they may not be right.

- Diversity, different skills and perspectives are valuable on the board – including younger, digitally savvy members.

- Board members should hold each other to account and police their own behaviour in meetings, rather than leave it entirely to the chair.

- More energetic constructive debate would be welcome – to do this focus on teamwork skills and be aware of the way groups, including boards, behave as social entities (social group dynamics).

- After board meeting decisions are made, disagreeing individual board members should not then try to overturn or shape decisions by ‘just having a word’ with the Chair or CEO.

- Ask probing questions so board meetings can review and critique proposals properly as a team, rather than individual members staunchly advocate for a particular position. Think of the decision process as ‘intelligent stress testing’ rather than leaving it as ‘sounds like a great idea.’ That process makes it more likely a decision owned by the board who will then have the CEO’s back when challenges arise.

- CEO succession planning – remember to consider your own organisation’s internal rising talent.

- Strong partnerships between Boards and CEOs are invaluable to the organisation, where there is mutual respect, energetic commitment to the organisation’s success and strong bonds of trust.

Making Effective Use of Sub-Committees

To help manage the amount of business a board has to deal with, you could consider setting up sub-committees – e.g. a risk committee, investment committee, audit committee, fundraising committee, nomination, governance or human resources committee.

Sub-committees can help:

- give more detailed attention to a specific area that a full board meeting hasn’t got time to consider

- share the workload amongst members

- address potential conflict of interest – e.g. executive remuneration

- streamline full board meetings

The full board remains responsible for the work of sub-committees. Clear terms of reference and a regular review of progress are important.

Cautionary Tales!

Reprinted from Charities Services Annual Review 2017/18. Department of Internal Affairs, pg 13

“This year, Charities Services completed a number of investigations including looking into the activities of two registered charities where we received complaints that those in senior management and officer positions were receiving substantial personal benefits. The complaints alleged that charity funds were being used on excessive salaries, private club memberships, improper use of vehicles, expensive annual dinners, additional leave and unnecessary international travel.

We recognised that both charities had a history of success and provided a benefit to those they were set up to support. What concerned us was that after looking into their activities, there appeared to have been a culture of complacency developed toward the existing management and governance processes. Neither organisation was able to provide adequate records to support and justify the use of charity funds for travel, leave, entertainment and memberships. In both cases we established that management and governance processes were either not being followed or did not exist.

We acknowledge that it is appropriate for a charity to reward high performing staff with salaries and bonuses at a competitive market rate, however the officers of a charity must ensure that decisions are well documented, and that contracts and agreements are up-to-date. In these cases, the absence of good records made it difficult to determine if the officers were considering their fiduciary duties when governing the charities. Commendably, both charities cooperated with us throughout the investigations, responding to requests for information and engaging with us effectively to talk about our concerns.

As a result, both charities went through major review processes to improve internal policies and processes to ensure management and governance practices improved. At the conclusion of both investigations, we determined that the spending itself did not represent a misuse of charity funds but that the shortcomings in the management and governance may have constituted gross mismanagement which is considered serious wrongdoing under the Charities Act. We issued both charities with ‘Letters of Expectations’ outlining our findings and reminded them of our expectations that officers put their fiduciary duties at the forefront of their decision making.

These case studies are good examples of a graduated use of our regulatory responses. While at the far end of the scale is deregistration, our first position is always to engage and work with charities to help them achieve and maintain compliance with the Charities Act.”

9. Board Integrity and Accountability

Boards need to act with integrity, be transparent and be accountable to their stakeholders, including staff and volunteers.

They need to ensure they have a good flow of information to help make decisions and are safeguarding the integrity of financial statements and other key information.

Boards need to have reports that give a good sense of:

- How the organisation is tracking against its purpose and plans

- Its financial health

- Major strategic project reports

- Updates on any material risks

- Any important regulatory compliance and reporting obligation matters

How much detail and structure of reports depends on the size, nature and complexity of your organisation’s operations. A small organisation should, at a minimum, see expenditure against budget, cash flow projections and a current balance sheet. The board is responsible for overseeing the integrity and assurance of the organisation’s financial position, performance and reporting.

To do this board members should have an appropriate level of financial literacy (be able to read a financial statement). Boards should draw on external financial expertise to help and establish an internal audit function.

If you are a registered charity there are specific requirements that you must meet. More information is on the Charities Services website. https://www.charities.govt.nz/new-reporting-standards/

Resources:

Qualities of an effective charity – Community Net Aotearoa

Guide: How to use a conflict of interest register – Charities Services

10. Engaging with Stakeholders and Community

The Board has an important role in helping the organisation engage effectively with stakeholders and the broader community.

Your CEO may have a good reputation and be working effectively with stakeholders. Good governance provides a solid foundation to enhance that. Stakeholders are people, groups or organisations with an interest or concern in your organisation. They may be clients, donors, employees, creditors, volunteers, government (and agencies), members, suppliers, unions, other related institutions and the broader community.

Engaging purposefully with stakeholders will be beneficial because:

- It will help strengthen relationships with stakeholders and you will find out what is important to them

- You will find out how your organisation is perceived

- It will improve the chances of you delivering what is needed

- You will gain access to more knowledge, resources and benefactors

It is especially important if you are considering changing purpose or direction. Producing an annual report on the work and achievements of the organisation for distribution to members, volunteers and other stakeholders is good practice. Other engagement could be through briefing with stakeholders such as funding agencies or relevant government bodies, participation in community meetings and keeping open, respectful dialogue with other agencies.

11. FAQs

Contact us if you have a question not answered below.

What Is a Good Number of Board Members?

Around seven is considered ideal. If smaller, you lose the range of experience and opinion. The legitimate absence of one or two members from a meeting can mean serious loss of input into decision making and discussion. On larger boards individual contributions are harder to make and meetings can be more difficult to manage in a timely way. Also members may absent themselves, thinking they won’t be missed.

Should Staff Serve on the Board?

As a general rule, it is inappropriate for staff, including the chief executive to serve on the board of the organisation that employs them. Separating out means there is no role confusion, each can wear one hat and focus on their special contribution to the organisation. One way some deal with it is that the CEO does not have voting rights. Employees below the CEO should not be on the board because in effect they become both the CEO’s employee and employer, compromising the integrity of relationships for all concerned, including the board.

How Long Should Board Members Remain on the Board?

There should be a balance between those with enough experience to provide institutional memory and continuity and those members who bring fresh energy and new ideas. Organisations that have no limit to board members’ tenure and no electoral process are particularly vulnerable to having long serving members who may become ‘set in their ways’ and find it difficult or don’t want to step down. A three year term with one or two further terms before compulsory stand down is one way of dealing with this. Too much turnover can lead to instability and makes it hard for the board to gel as a group, so staggering retirement and recruitment of new members is a good idea.

What About Small Organisations with Working Boards and Few or No Staff?

In small organisations board members may be filling both governing roles and operational functions, especially in new organisations. Your new organisation might have a ‘management committee’ rather than a separate governance board. It is often just the reality of the situation, but clarity around roles and observing boundaries is very important, whatever stage you are at. Board members helping with operational tasks are acting as an operational volunteer, not as a board member offering assistance. If there is a CEO, they are answerable to that person, who must be able to direct or manage the board member volunteer in operational work. Whether you are a ‘management committee’ member or a trustee member on a Board, you need to remember you still have the same legal duties and responsibilities to the organisation, and need to govern in the best interests of the whole organisation.

How Often and How Long Should Boards Meet For?

The board should meet as often and for as long as it needs to carry out its governance duties. Every six weeks is a common cycle according to 9 ways Sports NZ. If boards meet infrequently it is difficult to keep in touch with the organisation’s operations and emerging issues. Members put discussions out of their minds, and it is hard to maintain continuity of thinking and decision-making. Trying to keep up through email or similar communication risks patchy, unsatisfactory input. Monthly meetings put pressure on staff responsible for reporting to the board and may also be too frequent for trustees. Infrequent meetings (e.g. quarterly or twice a year) mean the board will be out of touch and not provide sufficient operational oversight and support where necessary to either the CEO or to the chair. Meetings of less than two hours are likely to give insufficient time to consider strategic level issues, but longer meetings may mean getting embroiled in unnecessary detail.